Dr. Alex Liu (Yong-chuan Liu)

🌍 Arrival and Early Experiences I

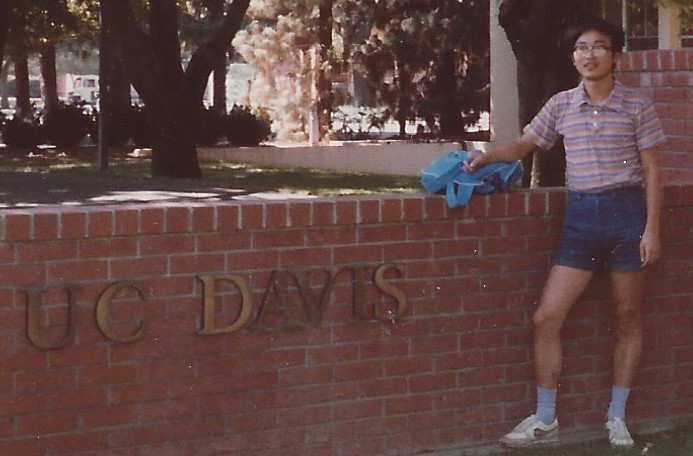

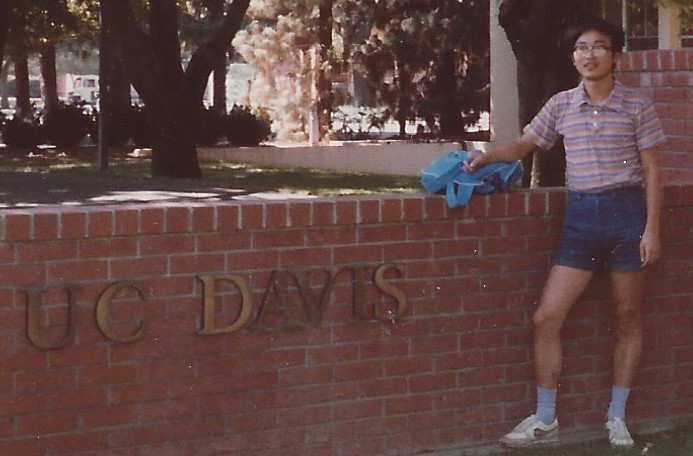

arrived in California from Beijing on June

20, 1986, as a Fulbright student. The

Fulbright Association arranged a

pre-academic program at the University of

California, Davis, where I spent the summer

studying English and American culture.

I

arrived in California from Beijing on June

20, 1986, as a Fulbright student. The

Fulbright Association arranged a

pre-academic program at the University of

California, Davis, where I spent the summer

studying English and American culture. In

October 1986, I formally entered Stanford

University and completed my doctoral program

on March 31, 1992. I took a one-year leave

during the 1989–1990 academic year, so in

total, I spent about four and a half years

studying at Stanford—not particularly long

in calendar years, but profoundly formative.After I obtained my degree, I worked as a

postdoctoral researcher at Stanford’s

Asia-Pacific Research Center. Later, I also

held a part-time position at the Hoover

Institution, where I engaged in comparative

research on political economy, technology,

and healthcare systems. Living near Stanford

for several years afterward gave me a sense

that I had spent much longer at the

university than the official record

reflects.

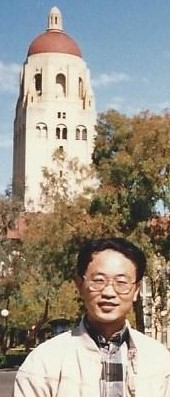

In

October 1986, I formally entered Stanford

University and completed my doctoral program

on March 31, 1992. I took a one-year leave

during the 1989–1990 academic year, so in

total, I spent about four and a half years

studying at Stanford—not particularly long

in calendar years, but profoundly formative.After I obtained my degree, I worked as a

postdoctoral researcher at Stanford’s

Asia-Pacific Research Center. Later, I also

held a part-time position at the Hoover

Institution, where I engaged in comparative

research on political economy, technology,

and healthcare systems. Living near Stanford

for several years afterward gave me a sense

that I had spent much longer at the

university than the official record

reflects.

🧭 Student Leadership and Civic

Engagement

Much like my experience at Peking

University in China, my time at Stanford was

deeply marked by community service and

student leadership—perhaps guided by the

same “spirit of service.” Many people

remembered me not just as a student, but as

someone committed to representing and

serving others—a so-called Chinese student

leader. In

1987, I was among the few who helped

revitalize the Association of Chinese

Students and Scholars at Stanford (ACSSS)

and helped establish a discussion forum on

social development issues. I also built ties

with Chinese organizations across the San

Francisco Bay Area, initiating collaborative

activities.

In

1987, I was among the few who helped

revitalize the Association of Chinese

Students and Scholars at Stanford (ACSSS)

and helped establish a discussion forum on

social development issues. I also built ties

with Chinese organizations across the San

Francisco Bay Area, initiating collaborative

activities. In

1989, after participating in Beijing’s

pro-democracy movement in April and May, I

returned to the U.S. in June, and in July I

was elected as the first president of the

Independent Federation of Chinese Students

and Scholars in the U.S. (IFCSS),

representing more than 40,000 Chinese

students and scholars nationwide. This role

gave me the chance to participate in major,

historic decision-making processes and to

exercise meaningful coordination and

leadership at both national and

international levels, during a critical time

for Chinese students and for U.S.–China

relations. IFCSS also pioneered the use of

early Internet and email tools to coordinate

national advocacy, a practice later examined

by researchers and journalists. This

experience anchored my early commitment to

applying technology for social good and

shaped my trajectory in social-tech

innovation.Through these initiatives, I began

to see how technology could be applied for

positive social impact—a theme that would

guide much of my later work. These efforts

also led me to receive several awards,

including recognition from the Media

Alliance and the National Graduate Student

Association of the U.S. Looking back, these

leadership experiences were groundbreaking

and socially impactful, laying an early

foundation for my later focus on

decision-support systems and data-driven

solutions, as well as seeking

human-values–guided principles for data

science and AI.

In

1989, after participating in Beijing’s

pro-democracy movement in April and May, I

returned to the U.S. in June, and in July I

was elected as the first president of the

Independent Federation of Chinese Students

and Scholars in the U.S. (IFCSS),

representing more than 40,000 Chinese

students and scholars nationwide. This role

gave me the chance to participate in major,

historic decision-making processes and to

exercise meaningful coordination and

leadership at both national and

international levels, during a critical time

for Chinese students and for U.S.–China

relations. IFCSS also pioneered the use of

early Internet and email tools to coordinate

national advocacy, a practice later examined

by researchers and journalists. This

experience anchored my early commitment to

applying technology for social good and

shaped my trajectory in social-tech

innovation.Through these initiatives, I began

to see how technology could be applied for

positive social impact—a theme that would

guide much of my later work. These efforts

also led me to receive several awards,

including recognition from the Media

Alliance and the National Graduate Student

Association of the U.S. Looking back, these

leadership experiences were groundbreaking

and socially impactful, laying an early

foundation for my later focus on

decision-support systems and data-driven

solutions, as well as seeking

human-values–guided principles for data

science and AI.

📚 Starting in Sociology—and a

Search for the Right Fit

When I entered Stanford in the fall

of 1986, I joined the Department of

Sociology to pursue a Ph.D. The department

was relatively small, but I had been drawn

by the work of two professors known for

their contributions to dynamic social

modeling. Upon

arrival, however, I discovered that one of

them had already left the university. The

remaining scholar, Professor Tuma, was

highly respected but primarily focused on

local dynamic model estimation, which

differed significantly from my research

interests.

Upon

arrival, however, I discovered that one of

them had already left the university. The

remaining scholar, Professor Tuma, was

highly respected but primarily focused on

local dynamic model estimation, which

differed significantly from my research

interests. Two

younger faculty members in quantitative

methods were still early in their careers

and showed little interest in the topics I

was passionate about. This mismatch left me

so uncertain that I even considered

transferring to another university. In fact,

I recall a scholar from the Chinese Academy

of Sciences who, drawn to Stanford for the

same reasons I was, left for Harvard after

less than a year.Ultimately, I chose to remain at

Stanford. I had grown fond of the campus,

the intellectual culture of the Bay Area,

and saw that switching departments might be

more feasible—and more fruitful—than

switching universities altogether.

Two

younger faculty members in quantitative

methods were still early in their careers

and showed little interest in the topics I

was passionate about. This mismatch left me

so uncertain that I even considered

transferring to another university. In fact,

I recall a scholar from the Chinese Academy

of Sciences who, drawn to Stanford for the

same reasons I was, left for Harvard after

less than a year.Ultimately, I chose to remain at

Stanford. I had grown fond of the campus,

the intellectual culture of the Bay Area,

and saw that switching departments might be

more feasible—and more fruitful—than

switching universities altogether.

🌉 Life Beyond the Department Remaining

in Silicon Valley offered me experiences I

had not anticipated but greatly valued. I

formed friendships through social and civic

activities, gained exposure to the world of

high technology—especially the tech

entrepreneurship culture—and also began to

explore spiritual and religious traditions.At Stanford, I attended Christian

fellowships for the first time, joined

interfaith dialogues, and, during a 1989

visit to Taiwan, met Master Hsing Yun at Fo

Guang Shan Monastery to discuss the role of

Buddhism in modern life.

Remaining

in Silicon Valley offered me experiences I

had not anticipated but greatly valued. I

formed friendships through social and civic

activities, gained exposure to the world of

high technology—especially the tech

entrepreneurship culture—and also began to

explore spiritual and religious traditions.At Stanford, I attended Christian

fellowships for the first time, joined

interfaith dialogues, and, during a 1989

visit to Taiwan, met Master Hsing Yun at Fo

Guang Shan Monastery to discuss the role of

Buddhism in modern life.

🎓 Broadening My Academic Pathways

Given

my strengths in methodology and statistics,

I was permitted to waive several required

courses. This allowed me to enroll in

advanced classes across Statistics, Computer

Science, and related departments. I

ultimately earned a Master’s in Statistical

Computing while also completing a wide array

of Ph.D.-level courses in Statistics.

Although I once seriously considered

transferring to the Statistics Department,

the time cost would have been considerable.

After consulting with mentors, I decided to

stay in Sociology to complete my Ph.D.—but

with a research agenda that increasingly

reflected my multidisciplinary journey and

interest in data analytics.

Given

my strengths in methodology and statistics,

I was permitted to waive several required

courses. This allowed me to enroll in

advanced classes across Statistics, Computer

Science, and related departments. I

ultimately earned a Master’s in Statistical

Computing while also completing a wide array

of Ph.D.-level courses in Statistics.

Although I once seriously considered

transferring to the Statistics Department,

the time cost would have been considerable.

After consulting with mentors, I decided to

stay in Sociology to complete my Ph.D.—but

with a research agenda that increasingly

reflected my multidisciplinary journey and

interest in data analytics.

🔎 Exploring New Methods: Decision

Trees and Latent Structures During

my Stanford years, two methodological areas

fascinated me most: decision tree models and

structural equation modeling (SEM),

including latent variables. These interests

drew me somewhat away from the traditional

center of gravity in Sociology, making it

difficult to find an ideal advisor within

the department.Fortunately, Stanford’s environment

was remarkably open, and my dissertation

committee was unusually supportive. It

included distinguished scholars such as

Professor Seymour Lipset, who had served as

president of both the American Sociological

Association and the American Political

Science Association. Their openness and

encouragement allowed me to pursue a

dissertation that was unconventional but

intellectually exciting.

During

my Stanford years, two methodological areas

fascinated me most: decision tree models and

structural equation modeling (SEM),

including latent variables. These interests

drew me somewhat away from the traditional

center of gravity in Sociology, making it

difficult to find an ideal advisor within

the department.Fortunately, Stanford’s environment

was remarkably open, and my dissertation

committee was unusually supportive. It

included distinguished scholars such as

Professor Seymour Lipset, who had served as

president of both the American Sociological

Association and the American Political

Science Association. Their openness and

encouragement allowed me to pursue a

dissertation that was unconventional but

intellectually exciting. I

focused my doctoral research on democratic

transitions, using data from more than 100

countries spanning the 1970s through the

1990s. I applied multiple advanced

statistical and mathematical models,

including decision trees—making me one of

the earliest to apply this method to

political science. I also experimented with

SEM and latent variable models, though this

work remained largely exploratory, since few

local experts specialized in it at the time.

I

focused my doctoral research on democratic

transitions, using data from more than 100

countries spanning the 1970s through the

1990s. I applied multiple advanced

statistical and mathematical models,

including decision trees—making me one of

the earliest to apply this method to

political science. I also experimented with

SEM and latent variable models, though this

work remained largely exploratory, since few

local experts specialized in it at the time.

🤖 Early Steps Toward Statistical

Learning and AI

In hindsight, the most

transformative technical lesson I gained at

Stanford came from the Statistics

Department: a deep engagement with

statistical learning. My exploration of

decision trees led directly into statistical

learning, which in turn opened the door to

machine learning—long before the field

became widely recognized.Earlier, at Northwestern

Polytechnical University in China, I had

focused on using mathematics to model social

problems. At Peking University, I approached

technology as a tool for addressing societal

challenges. At Stanford, particularly

through my immersion in statistics, I

refined this trajectory by applying

statistical computation to model and solve

complex social problems with greater depth

and precision.

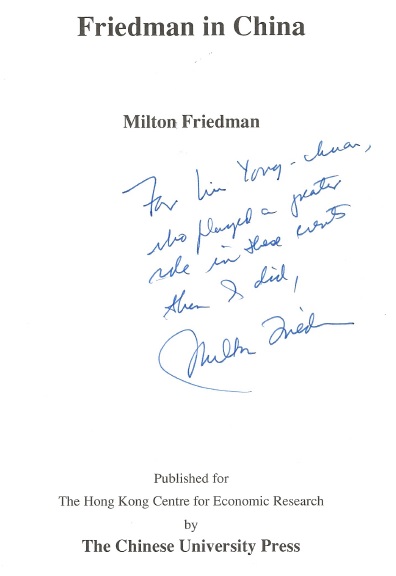

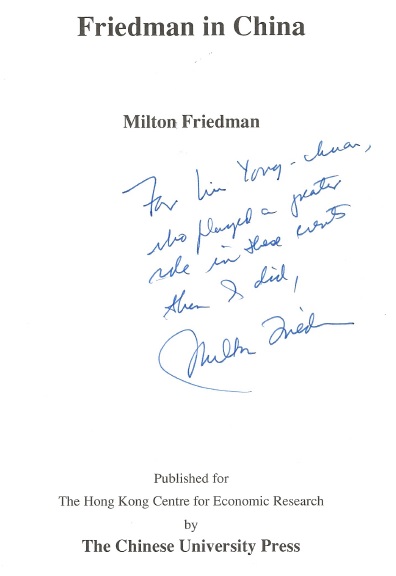

This

interdisciplinary approach gave me the

chance to interact with leading figures

across fields, including Nobel laureate

Milton Friedman. That encounter, in

particular, encouraged me to embrace a

multidisciplinary perspective—one that

blended social science with economics,

statistics, and computational methods.

This

interdisciplinary approach gave me the

chance to interact with leading figures

across fields, including Nobel laureate

Milton Friedman. That encounter, in

particular, encouraged me to embrace a

multidisciplinary perspective—one that

blended social science with economics,

statistics, and computational methods.

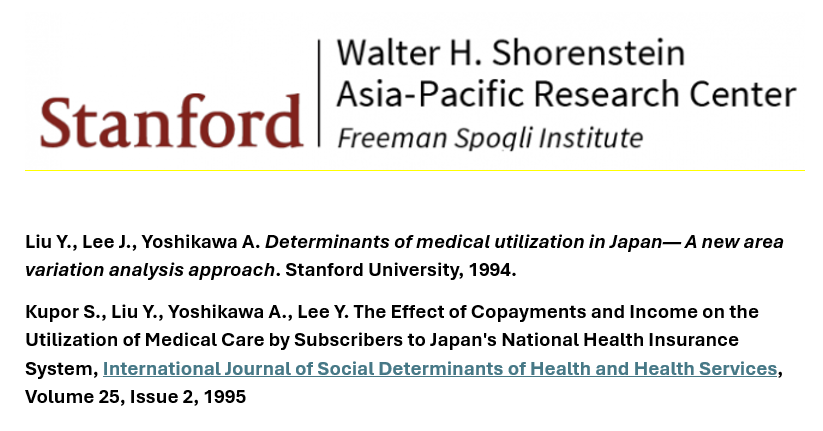

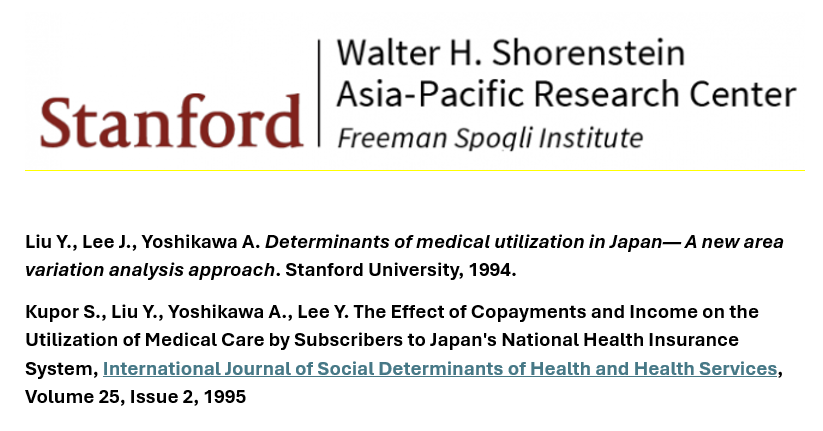

💼 Applied Research and Postdoctoral

Work After

completing my degree on March 31, 1992, I

secured a postdoctoral position at

Stanford’s Asia-Pacific Research Center,

where I modeled healthcare systems,

comparing the U.S. and Japan. Although

healthcare was not my primary interest at

the time, this experience sharpened my

comparative policy analysis skills and

multidisciplinary approaches. Soon after, I

shifted toward business decision-making

applications—including health-related

business and social policy—which became a

lasting focus of my applied research.Later, when I taught part-time at

the University of California and elsewhere,

it was always in business schools. This was

a natural fit, since business schools valued

the methods I had specialized

in—particularly decision trees, SEM, and

latent variable modeling—and placed a

stronger emphasis on decision making than

traditional sociology.

After

completing my degree on March 31, 1992, I

secured a postdoctoral position at

Stanford’s Asia-Pacific Research Center,

where I modeled healthcare systems,

comparing the U.S. and Japan. Although

healthcare was not my primary interest at

the time, this experience sharpened my

comparative policy analysis skills and

multidisciplinary approaches. Soon after, I

shifted toward business decision-making

applications—including health-related

business and social policy—which became a

lasting focus of my applied research.Later, when I taught part-time at

the University of California and elsewhere,

it was always in business schools. This was

a natural fit, since business schools valued

the methods I had specialized

in—particularly decision trees, SEM, and

latent variable modeling—and placed a

stronger emphasis on decision making than

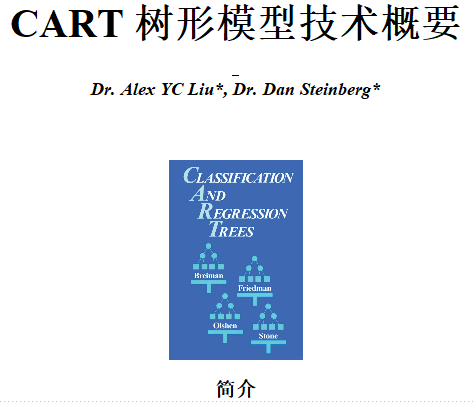

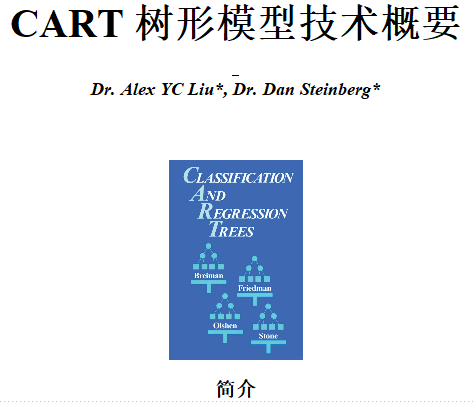

traditional sociology. During

this period, I was deeply influenced by the

1984 book

Classification

and Regression Trees,

authored by Jerome Friedman and colleagues

at Stanford. That work later inspired

Harvard Ph.D. Dan Steinberg to launch

Salford Systems, a company dedicated to

decision tree software. I had opportunities

to collaborate with them briefly. Salford

Systems was eventually acquired by MINITAB,

and some of its members later contributed to

the foundation of transformer-based AI

models, which underpin technologies such as

ChatGPT.

During

this period, I was deeply influenced by the

1984 book

Classification

and Regression Trees,

authored by Jerome Friedman and colleagues

at Stanford. That work later inspired

Harvard Ph.D. Dan Steinberg to launch

Salford Systems, a company dedicated to

decision tree software. I had opportunities

to collaborate with them briefly. Salford

Systems was eventually acquired by MINITAB,

and some of its members later contributed to

the foundation of transformer-based AI

models, which underpin technologies such as

ChatGPT.

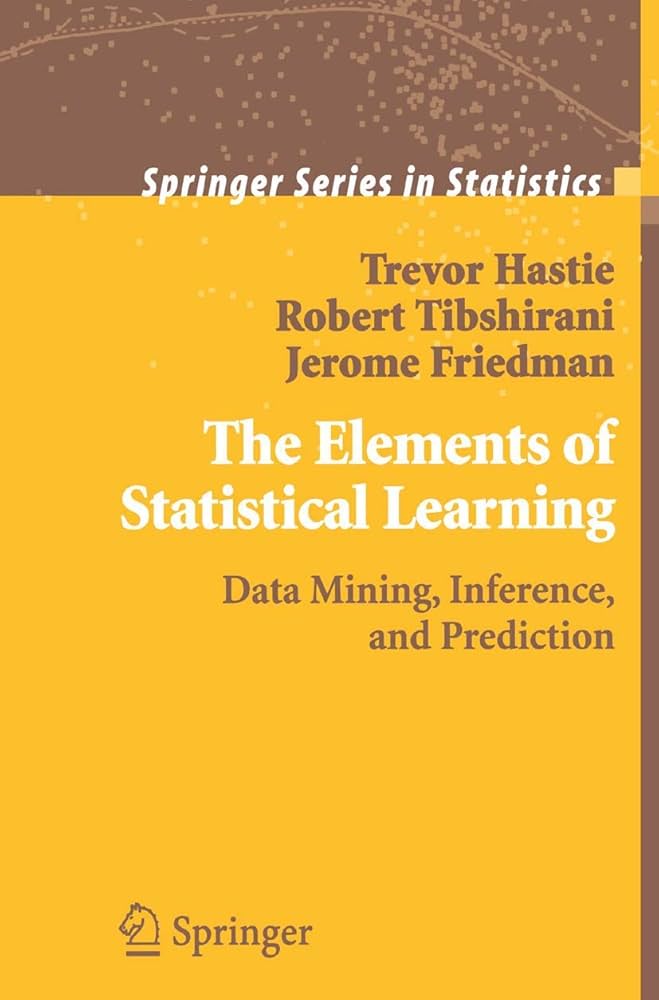

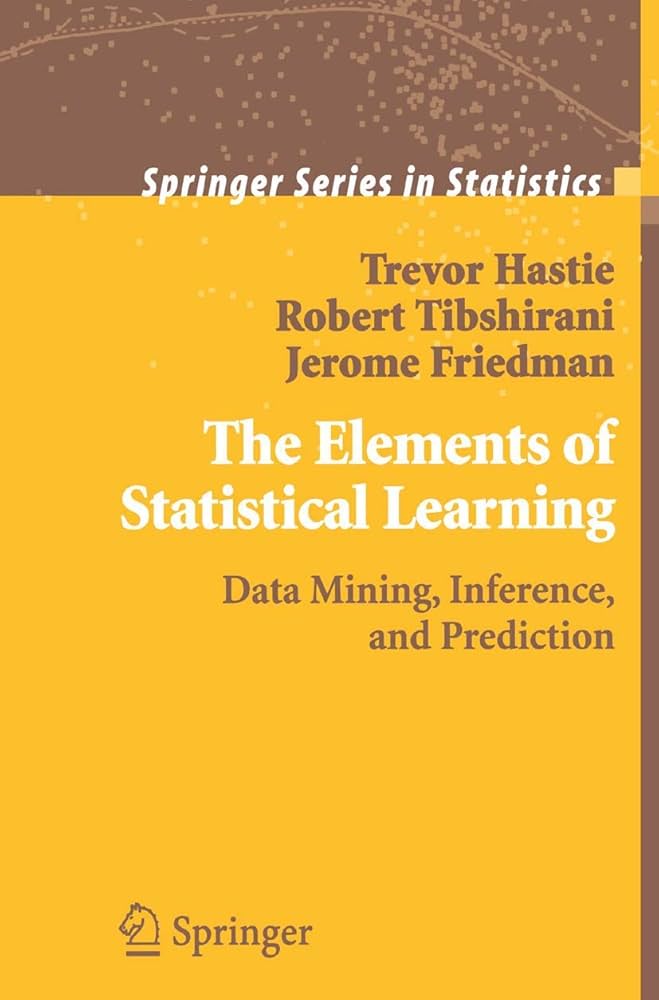

📘 Lifelong Commitment to

Statistical Learning

Although

my ties to the Sociology Department

gradually diminished, my connection to the

Statistics Department remained active. I

closely followed the work of Jerome Friedman

and his colleagues, especially their

influential textbook,

The Elements of Statistical Learning,

which became a classic reference in machine

learning. I used it extensively in my

professional work at IBM and in Spark-based

implementations.This long-term engagement allowed me

to advance steadily in statistical learning,

machine learning, and AI. To this day, many

assume I trained in Statistics or Computer

Science at Stanford, rather than Sociology.

While that misconception is understandable,

the truth is that my core motivation has

always been applied, socially relevant

research—using data science and AI to

address real-world social and human

challenges.

Although

my ties to the Sociology Department

gradually diminished, my connection to the

Statistics Department remained active. I

closely followed the work of Jerome Friedman

and his colleagues, especially their

influential textbook,

The Elements of Statistical Learning,

which became a classic reference in machine

learning. I used it extensively in my

professional work at IBM and in Spark-based

implementations.This long-term engagement allowed me

to advance steadily in statistical learning,

machine learning, and AI. To this day, many

assume I trained in Statistics or Computer

Science at Stanford, rather than Sociology.

While that misconception is understandable,

the truth is that my core motivation has

always been applied, socially relevant

research—using data science and AI to

address real-world social and human

challenges.

🧠 A Foundation for AI in Social

Science and Healthcare

My years at Stanford from 1986 to

1992 were transformative. They built the

foundation for my later work in AI for the

social sciences, particularly in healthcare

policy and management AI. The

interdisciplinary training I received

combined the perspectives of sociology,

statistics, and computational methods. It

also gave me early opportunities to apply

decision trees and SEM to complex political

and policy problems, while laying a

technical foundation in statistical learning

and machine learning.Equally important, my leadership

experience—whether in student organizations,

national associations, or comparative policy

research—helped me learn how to connect

data-driven insights with real-world

governance needs, guided by human values.

This balance of technical rigor and

practical relevance, anchored in human

values, continues to guide my career to this

day.

The

interdisciplinary training I received

combined the perspectives of sociology,

statistics, and computational methods. It

also gave me early opportunities to apply

decision trees and SEM to complex political

and policy problems, while laying a

technical foundation in statistical learning

and machine learning.Equally important, my leadership

experience—whether in student organizations,

national associations, or comparative policy

research—helped me learn how to connect

data-driven insights with real-world

governance needs, guided by human values.

This balance of technical rigor and

practical relevance, anchored in human

values, continues to guide my career to this

day.

Much like my experience at Peking University in China, my time at Stanford was deeply marked by community service and student leadership—perhaps guided by the same “spirit of service.” Many people remembered me not just as a student, but as someone committed to representing and serving others—a so-called Chinese student leader.

When I entered Stanford in the fall of 1986, I joined the Department of Sociology to pursue a Ph.D. The department was relatively small, but I had been drawn by the work of two professors known for their contributions to dynamic social modeling.

In hindsight, the most transformative technical lesson I gained at Stanford came from the Statistics Department: a deep engagement with statistical learning. My exploration of decision trees led directly into statistical learning, which in turn opened the door to machine learning—long before the field became widely recognized.Earlier, at Northwestern Polytechnical University in China, I had focused on using mathematics to model social problems. At Peking University, I approached technology as a tool for addressing societal challenges. At Stanford, particularly through my immersion in statistics, I refined this trajectory by applying statistical computation to model and solve complex social problems with greater depth and precision.

My years at Stanford from 1986 to 1992 were transformative. They built the foundation for my later work in AI for the social sciences, particularly in healthcare policy and management AI.